As reported in our August 2023 newsletter, Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) has recently become mandatory for all development (with some minor exceptions). Chartered Town Planner Richard Pigott, Director, at Planning & Design Practice provides an update on what this will mean for applicants, landowners and homeowners.

One of the key features of BNG is the statutory target to increase the biodiversity value of a site by 10% for a minimum of 30 years, through a habitat management and monitoring plan. Originally expected to become law in November 2023, it took effect for large sites from February and for small sites from 2nd April 2024. There is still some uncertainty and skepticism about how it will work in practice or whether it will achieve the stated aim of reversing the loss of biodiversity. However, it is now law and cannot be ignored by applicants and local planning authorities.

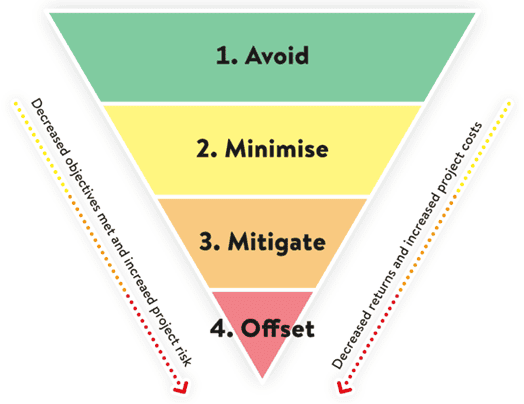

BNG in England is founded on the mitigation hierarchy, which is detailed in the National Planning Policy Framework. In a nutshell, the hierarchy presents a sequential approach to addressing potential harm to biodiversity when determining planning applications. It emphasises the prioritisation of avoidance first, followed by mitigation measures, and lastly, compensation. In other words, if BNG can be achieved on site it should be, with off site compensation or ‘offsetting’ a last resort.

Effects of Mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain

The effects of mandatory BNG are numerous but, from a developer’s perspective, are likely to include the following:

- The achievement of BNG on site will, in many cases, reduce the developable area of the site as existing habitats, particularly more valuable ones such as hedgerows, trees and wetlands, may need to be retained;

- The achievement of BNG off site involves the use of biodiversity net gain offsetting mechanisms, such as the creation or enhancement of off-site habitats, purchasing biodiversity units on the market, or acquiring statutory credits. There is an emphasis on securing offsite solutions as close to the impact as possible;

- It is prudent to involve ecologists early on in the design process in order to understand the baseline habitat and what ecological features are important in the ‘biodiversity metric’. It will then often be an iterative process to determine the best way to develop a site;

- Whichever way BNG is to be achieved for a given site, there will be an increased financial burden on developers both at the application stage (ecological fees and often also legal fees) and in the long term as management plans lasting at least 30 years will need to be adhered to. This may, in turn, affect the viability of schemes.

With regards offsetting solutions, as well as market leaders in the private sector such as Environment Bank, some local authorities and Wildlife Trusts are developing their own habitat banks. Derbyshire Wildlife Trust, for example, is offering Derbyshire-based BNG units available now, with Section 106 legal agreements in place. More information can be found here: www.wildsolutionsdwt.co.uk

Whilst mandatory BNG is not an overnight concept, it certainly seems to have gone under the radar for many of our clients and eyebrows are often raised when we tell them what it could mean for their proposals. If you wish to discuss this issue further please do not hesitate to get in touch on 01332 347371 or email enquiries@planningdesign.co.uk.

Richard Pigott, Director – Chartered Town Planner, Planning & Design Practice Ltd