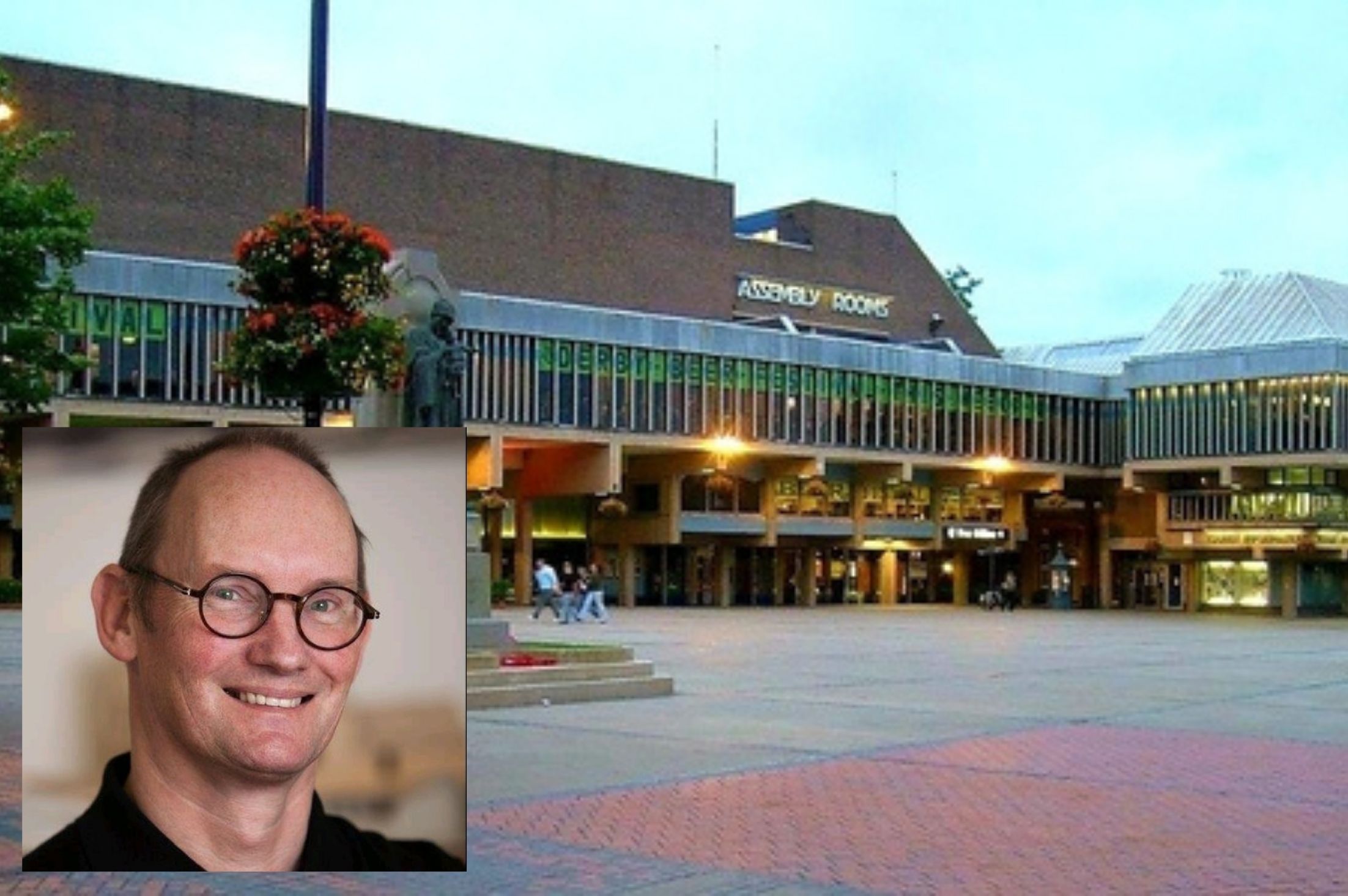

As Evans Vettori celebrate their recent awards success with The Lyth Building for Nottingham Trent University, which was awarded the RIBA East Midlands Building of the Year Award 2022, we asked their Founder, Rob Evans about his favourite building and architectural inspirations. Here he discusses the many merits of the Grade II* Listed Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, designed by Architect Frederick Gibberd following a global competition.

1967: England had won the World Cup, Liverpool F.C. were champions of England, The Beatles had just released Sgt.Pepper – and I was taken by my family to a new Cathedral, the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King . As an 8-year-old ‘Thunderbirds’ fan, this futuristic architecture encapsulated a palpable sense of optimism. I actually looked forward to going to mass there and was once so excited running around, that I cut my head on the corner of William Mitchell’s beautiful bronze door, thereby sealing a visceral relationship. I love it not just for its spiritual beauty but also for its amazing story.

After Lutyens ‘30s design for the second biggest cathedral in the world was finally abandoned, a design competition was held. It attracted a staggering 293 entries. Frederick Gibberd (a non-Catholic) prevailed against the likes of Lasdun with a design rich in symbology, simply expressed the latest thinking from Rome: ‘’All the faithful should be led to that fully conscious and active participation in liturgical celebration’ (Second Vatican Council ’62-’65). Cardinal Heenan’s letter to the competitors exhorted ‘The high altar is not an ornament to embellish the cathedral building. The cathedral, on the contrary, is built to enshrine the altar of sacrifice.’ Gibberd’s simple design concept (often compared with Neimayer’s 1960 Cathedral of Brasilia) was a ‘precise geometry rising from rocky surroundings’. His central crown symbolised Irish kingship rising above the protestant merchants on the dockside.

During construction Taylor Woodrow’s single tower crane, revolving slowly upwards, was visually perhaps the most splendid piece of contractors’ tackle seen in England since the war. The huge angled ribs, reaching for the sky as the frame went up, perfectly expressed its lofty purpose.

At architecture school there was a truism that every student had to design a circular building to ‘get it out of their system’. At Liverpool however the circle works wonderfully to create a simple focused space, which is hard to convey with photography. Attending a sung mass is the only way to fully appreciate the majestic synthesis of volume, light and sound.

One of my favourite ideas is the curved ramp which leads the procession up from the presbytery in Lutyens’ crypt. The giant organ strikes up and is joined from below by a sublime choir. Soon the cross appears over the parapet, closely followed by the tall Bishop’s hat. Pure theatre, and a poetic way to link 60’s modernism with 30’s neo-classicism. Another favourite part is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament – a perfect fusion of modern art and architecture. Ceri Geraldus Richards’ pale blue and yellow stained glass washes heavenly sunlight over his abstract painting. Sixteen radial bays contain a variety of chapels and the main entrance. I have always enjoyed these subtle variations around the perimeter – miniature Corbusian spaces in their own right.

In the middle of the volume, the thorny baldacchino, with its sophisticated battery of audio equipment, succeeds admirably in spatially linking the altar with the lantern high above. The subtly dished floor means that a (rare) congregation of 2,000 can all see the alter, yet there is still a sense of intimacy for the more regular small congregation.

On completion the Cathedral’s ‘scale-less’ interior received criticism in the Architectural Review (Jun 1967). The ‘brutally’ bare concrete soffit rather reminds me of the concrete Pantheon dome, standing in stark contrast to Piper’s brightly coloured stained glass. The AR did allow that it was admirable that the architect should have had such humility as to allow his cathedral to be ‘tampered with’ by its users.

Sadly ‘60s optimism proved short-lived, and the Cathedral came close to being demolished after mosaic tiles fell off and leaks appeared in the innovative aluminium roof. I don’t envy Gibberd the lawsuits that followed. He was sued by the church for £1.3m, and eventually the roof was replaced with stainless steel.

With dwindling congregations and income, the days of such grand church projects now seem to be over. The biggest church project our practice has designed was a community hall. This won ‘Best New Church Building’ in 2014 – a sobering illustration of the lack of church building. I may never design a church, but the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King will remain a powerful symbol of optimism in modern architecture.

Robert Evans, Founding Director, Evans Vettori