Harry Capstick, part of the PDP Planning team takes a look at urban uplift, what it is and what it means for the planning system.

On 6 August 2020, the government published ‘Changes to the current planning system’. The consultation paper set out four policy proposals to improve the effectiveness of the current system.

In changes to the current planning system, the government set out the importance of building the homes our communities need and putting in place measures to support our housing market to deliver 300,000 homes a year by mid-2020s.

It has been decided that the most appropriate approach to meet this figure is to retain the standard method in its current form. However, in order to meet the principles of delivering more homes on brownfield land, the government have applied a 35% uplift to the post-cap number generated by the standard method to Greater London and to the local authorities which contain the largest proportion of the other 19 most populated cities and urban centres in England, and have referred to these places as the ‘Urban Uplift’. This is based on the Office for National Statistics list of Major Towns and Cities, ranked in order of population size using the latest mid-year population estimates provided by the Office for National Statistics.

The “Urban Uplift” has now been a material consideration in the determination of planning decisions since June 2021. Two early appeal decisions, both in Sheffield (Deepcar PINS 267168 and Loxley PINS 3262600), have provided an indication as to the implications of the uplift and how it should be applied.

The City Council ran the argument that the Urban Uplift, introduced by changes to the NPPG in December 2020, should not be applied at the date 6 months after its introduction as stated in the NPPG (i.e. 16 June 2021), but only at a time when the Council decided to publish its next updated Monitoring Report, as this allowed the timescales to be aligned. Neither Inspector found this argument to be persuasive, stating that there are no provisions to opt-out of avoiding the effect of the uplift from this date. The Council also sought to argue that the increased number of dwellings could only be delivered in the main urban area and not in other settlements within the City’s boundary.

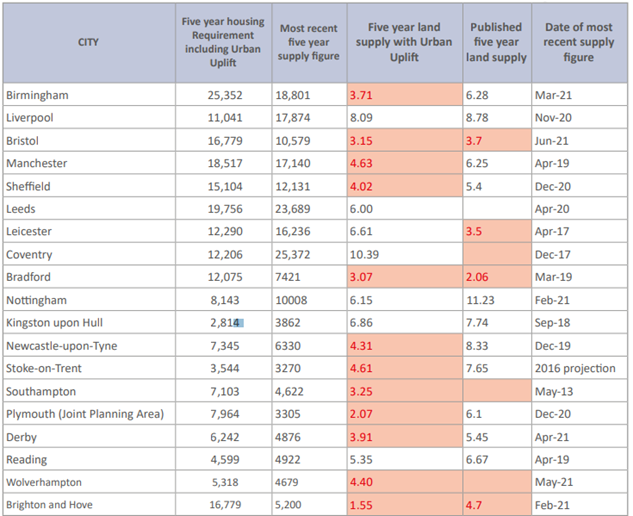

Again this was rejected by the Inspectors. These appeals also confirm that Councils are required to demonstrate that student accommodation will have a positive impact on the supply of market housing, and that such accommodation cannot just be taken into account, with no adequate analysis. In relation to what this means for the other 20 areas, which are subject to the Urban uplift, this is set out in the Table below.

The application of the urban uplift to the most recently published land supply figures results in the following authorities no longer having a five year supply:

Birmingham (3.71), Bristol (3.15), Manchester (4.63), Sheffield (4.02), Bradford (3.07), Newcastle-upon-Tyne (4.31) Stoke-onTrent (4.61), Southampton (3.25), Plymouth (Joint Planning Area) (2.07), Derby (3.91), Wolverhampton (4.40), and Brighton and Hove (1.55).

With the exception of Bristol, which has a 20% buffer, all of the other areas have a 5% buffer. For 7 authorities, this change would mean that the “tilted balance” is engaged as it was before. For a smaller number of authorities, that change away from a local plan target, would actually result in demonstrating a more than five year land supply. Of course, this analysis just utilises the Council’s most up to-date published information, and as the recent appeals in Sheffield demonstrate, these can in themselves be subject to substantial discounting, depending upon the approach adopted in the collection of evidence by the Council.

Harry Capstick, Planner, Planning & Design Practice Ltd