In an article written for Derbyshire Life “Tales from the city”, Jon Millhouse, a chartered town planner, member of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation and specialist in heritage and conservation at Planning & Design Practice Ltd, explores Derby’s industrial past.

Rivers have been central to our human story since time immemorial. They have given us water, food, protection, connectivity, trade and industry. They have determined the location and shape of our towns and cities.

Derby is no different. In fact, there are few stretches of water which offer as much historical interest, as the River Derwent through Derby. And yet, Derby has for many years turned its back on and ignored its river, despite it running through the heart of the city.

2021 is an important year for the River Derwent in Derby. It marks the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Derby Silk Mill, and the present building opens its doors to the public once again as a “Museum of Making”. It also sees a regular boat service return to Derby for the first time this year in decades in the form of a riverboat between Exeter bridge in the city centre and Darley Abbey Mills a mile upstream.

I decided to walk this fascinating route, to admire its buildings and bridges, and contemplate its history, interest, and intrigue.

My journey starts beside the majestic Council House, an example of 1930s neoclassicism overlooking the little used and underappreciated river terrace. In front of the Council House the graciously curving river basin creates an expansive and calm body of water which looks as though it was created for picturesque, reflective effect, but was in fact like much else in this area a product of an industrial past.

On the north side of the basin, the solid looking stone-built Exeter Bridge looks monumental and capable of withstanding a siege, as if marking an important crossing point, but is little used nowadays having been superseded by later concrete structures. The pillars of the bridge are adorned by motifs of local luminaries, Herbert Spencer, (Philosopher), Rasmus Darwin, (Physician, Botanist and Poet) and John Lombe (Founder of the Silk Mill).

On the eastern bank is Exeter House, an attempt at a modernist apartment block, with its “streets in the sky” balconies and communal green space overlooking the river. But with it’s bright red front doors and chimney pots it is not the purest example of modernism -more Leytonstone than Le Corbusier!

The Council House, Exeter House, magistrates court and adjacent roundabout were all part of the 1931 central improvement plan by Derby Council Architect Charles Herbert Aslin. It is ironic that the roundabout -a feature beloved by mid-twentieth century municipal planners -survives as an ornamental centrepiece despite having little practical use given traffic restrictions on nearby roads. This was an era when the confidence and power of the urban planner was at it’s peak. The old world boldly swept away to be replaced with new ways of living and working.

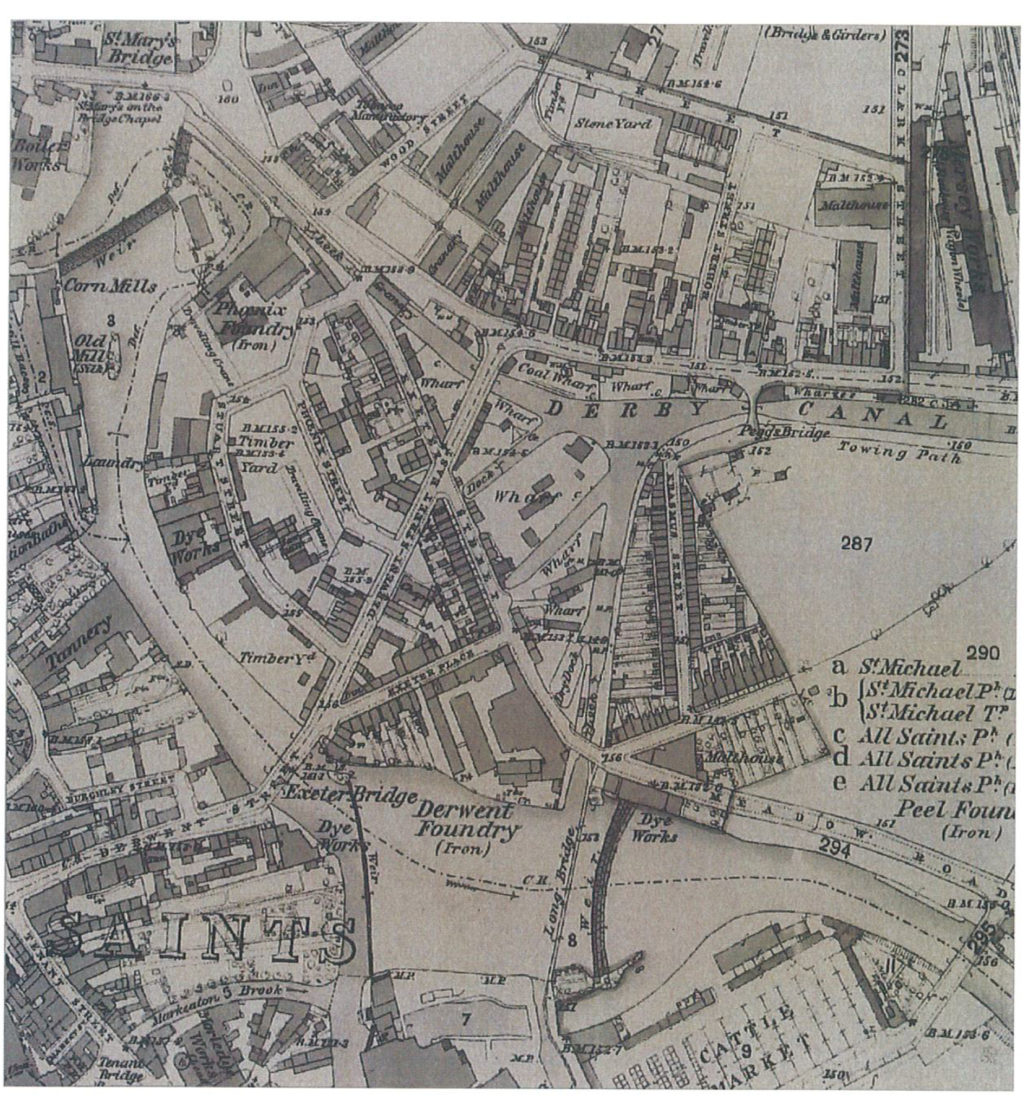

North of the river there is a forlorn looking piece of land sandwiched between the river and the monolithic ring road known as ‘North Riverside’. Earmarked for redevelopment projects for years which have never quite happened, it now seems disjointed and unloved. Look at a late 19th century map however and a very different picture is painted -one of canal docks, wharfs and tightly packed terraced housing. You can almost imagine the hustle and bustle of the dockyards, kids in rags playing by the canal, and thirsty workers drinking in the pubs and fighting in the street. The Exeter arms survives as a remnant -if only its walls could talk!

Beyond Exeter Bridge a newly built Premier Inn hotel overlooks the river on the site of what was once a grand townhouse known as Exeter house, where bonnie Prince Charlie famously signed documents to concede the retreat of his invading Jacobite army in 1745. The prince travelled through Derbyshire on route to London not because he was anticipating a Premier Inn, but because he was anticipating the people of Derbyshire to be sympathetic to his cause and willing to take arms and join the march South. It is hard to imagine Derbyshire as a hotbed of Scottish nationalist fervour -unless perhaps Scotland do well in the European football championships this summer.

A modern footbridge affords a pleasant view of the famous Silk Mill, a rebuild of the original mill constructed between 1718 and 1721 for John Lombe. Revolutionary in its day for its scale and use of technology, Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, famously visited Derby in 1720 and stood in awe at the sight of it. The Silk Mill is considered by many to have been the world’s first factory, yet until very recently it was less celebrated than Arkwrights and Strutts Mills further up the Derwent valley at Cromford and Belper. Granted, the present Silk Mill building is a rebuild (although remnants of the original survive beside the river), but the Silk Mill was a good half century earlier than its more illustrious neighbours. It also has the added benefit of a Hollywood-esque spy story. Italian authorities reputedly sent an assassin to kill John Lombe for industrial espionage, having himself apparently stolen silk throwing secrets after a visit to Piedmont. Lombe dies suddenly in 1722. It is good to see the building having finally undergone restoration and transformation into to a public museum, the new Museum of Making, part of the Derby Museum portfolio.

Another building which is undervalued, and overdue restoration is St. Mary’s Bridge Chapel. One of only a handful of its type in the country, the mediaeval bridge and chapel present an evocative riverside vista, celebrated in 19th century paintings but now sadly dominated by the thousands of vehicles rumbling passed daily on the concrete flyover built in the 1970s just feet away.

On past the remnants of old Victorian factories and foundries, developed when Derby was the workshop to the world and supplying materials for notable buildings such as Bombay Pier and London’s Albert suspension bridge.A symbol of the brute strength and power of the area’s industrial past survives in the form of Handyside Bridge, a stout but nevertheless gracious iron bridge, once taking steam engines but now enjoyed by pedestrians.

To the west is Strutts Park, a pleasant suburb of late nineteenth/ early twentieth century houses, some in the arts and crafts style, on the site of the original Roman settlement in Derby.

Into Darley Park, a wonderfully attractive green lung, made more accessible by a recently constructed riverside path. This is classic English parkland from the old Darley Hall, gracefully sweeping down to the river and framed by specimen trees. The hall is long gone but its terrace survives as a cafe, offering a celebrated view back to the cathedral -if only the tower of a recently built hotel didn’t jostle for your attention.

On the opposite side of the river is the suburb of Little Chester, so named in recognition of it being the location of Derby’s second Roman settlement -Derventio. Remnants of the Roman settlements were recently uncovered in an archaeological dig which preceded the construction of a flood defence wall. The wall was then rather pleasingly built to follow the original perimeter wall of the Roman fort, complete with pillars to mark the entrance and narrow Roman style bricks.

The Evans family who built Darley Hall made their fortune from cotton spinning in the adjacent Darley Abbey Mills. The associated workers community survives today as a much sought-after London style ‘urban village’. Clusters of former millworkers cottages exist as if in a time capsule. Once a place of overcrowding and hard, gritty lives I’m sure, but today quaint and benign.

A remnant of the Cistercians Abbey which predicated the mill still exists as a popular drinking establishment, albeit currently closed.

Over the river the mill complex itself is a hub of activity -creative businesses, studios, artisan eateries, local people milling about.

Here the river boat -and this particular walk- terminate. A short stretch of river but 2000 years of history and much to admire

“Tales from the city” was originally written for, and appeared in Derbyshire Life – Volume 90 Issue 7, July/ August 2021