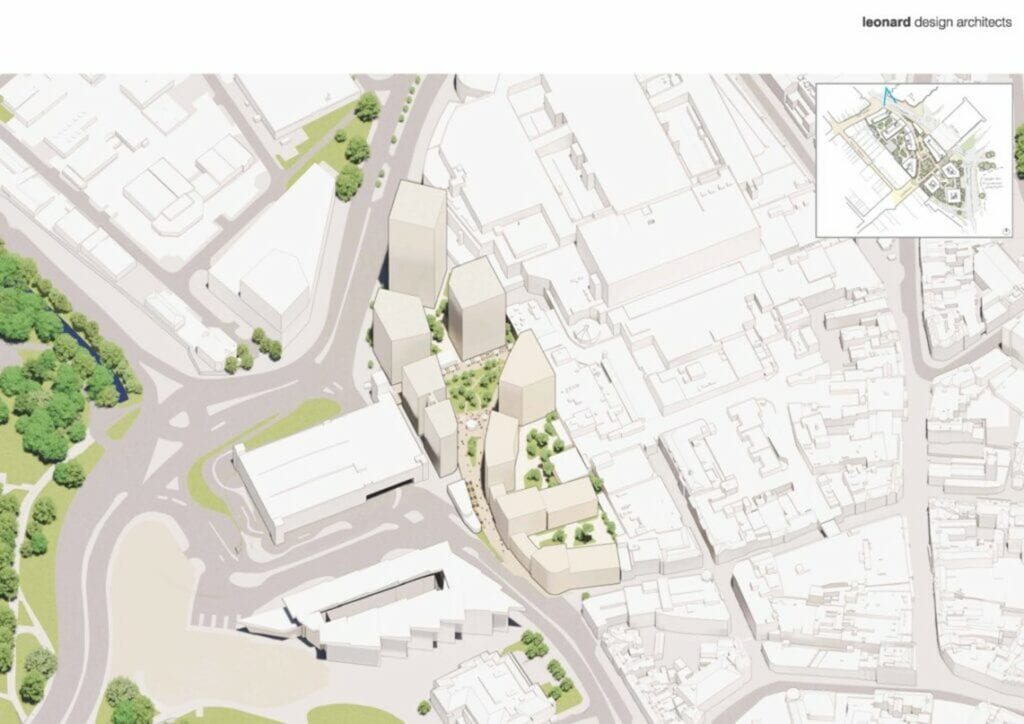

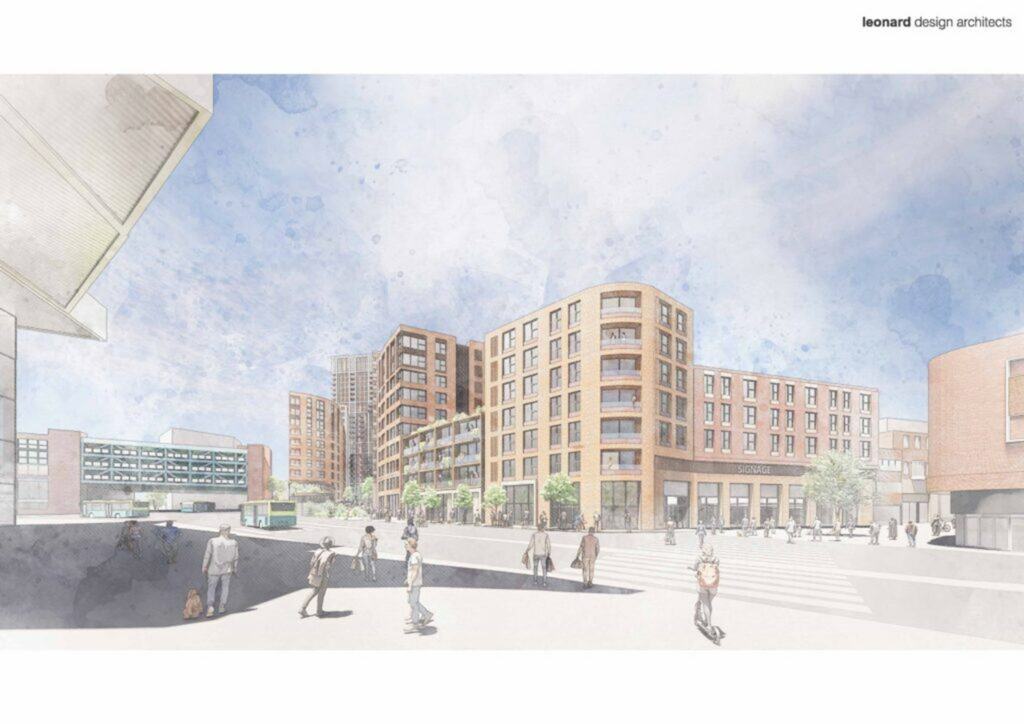

Proposals for high-rise development in Derby city centre are once again attracting attention and controversy, write Richard Pigott and Megan Askham of Planning & Design Practice. The source of the latest controversy comes in the form of Derbion’s plans for the demolition of the Eagle Market building, public house and Derby Theatre, and the erection of a phased mixed-use development; and a separate application to demolish Bradshaw Way Retail Park and build five buildings for housing, commercial premises and office space. Perhaps the most eye-catching element was an apartment block that would be up to 29 storeys high.

The plans received the Council’s backing after seven out of ten councillors voted in favour of the proposals. But the plans must now be referred to the Government due to an objection made by Historic England (HE) who have been critical of the scheme. If the Government approves, Derbion will be able to press ahead with more detailed plans in due course.

Well, these are the headlines anyway, but we were curious to examine the concerns raised by HE, and examine how they were addressed by the council as well as gauge local opinion on what effect these proposals might have. The application is in outline only (detailed designs to follow) but some fairly detailed 3D visuals have been produced, providing an indication of what the development could entail.

Historic England, as a statutory consultee, provided a detailed response, raising concerns about the impact on the setting of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site (DVMWHS), a number of listed buildings and conservation areas. For those who may not be familiar with the term, setting is defined as “the surroundings in which a heritage asset is experienced”, hence it can extend well beyond the asset’s physical structure and immediate surroundings. As part of any planning proposal, it is always necessary to determine what impact a proposal might have on the setting of heritage assets.

HE’s objections can be summarized as:

- Adverse impact on DVMWHS by virtue of harmful impact on the skyline, townscape and scale of the surroundings from the vicinity of the Silk Mill at the southern end of the WHS

- Adverse impact on the Grade I Cathedral Church of All Saints, by virtue of the outline proposal having the potential to compete with the prominence of the Cathedral tower as a key historic and cultural landmark

- Adverse impact on the Friar Gate Conservation Area by virtue of acting as a highly visible and jarring new addition to powerful vistas from the Conservation Areas towards the city centre

- Adverse impact on the City Centre Conservation Area as the outline proposals will have a high impact on powerful vistas

- Ignoring the Tall Buildings Study, which recommends a building of no more than 12 storeys on the site, with the proposal for a tower of well over twice this height, thus eroding the Derby skyline and changing the character of the cityscape.

In response to these concerns, the planning officer’s report stated that:

- Given the scale and height of the proposed development and its impact on the city’s skyline, there is a potential for the development to have an impact on a number of designated and non-designated heritage assets that reside within the site’s wider context

- With respect to the DVMWHS, consideration must also be given to the other heritage assets in the vicinity of the site. From longer-range views, one can appreciate the land levels of the city and the elevated position of the historic core, therefore, given the scale of the proposal, the taller elements of the development will be visible from above the townscape.

- The development would protrude above the skyline along Friar Gate which is a direct result of the height of the tallest blocks rather than the proposed development as a whole. However, consideration should be given to the changing land levels.

- The majority of heritage assets are located to the west of the application site and there will be a clear interaction between the development and these assets, including Conservation Areas and listed buildings

- The heritage consultees echo each other’s concerns that the development will have a degree of harm, some stating that this would be a considerable degree of harm to the heritage assets. The development would also dramatically alter the character of the cityscape, forming a key part of the setting of these heritage assets.

The officer report concluded that there would be some harm to heritage assets but that the public benefits would outweigh this harm.

This application provides further evidence of HE’s position as an influential consultee with the power to delay and potentially prevent development where they identify heritage harm.

In the specific case of Derby, the Tall Buildings Study does identify key views and vistas although these are meant to assist with planning decisions rather than being ‘protected views’ as such.

High-rise and heritage

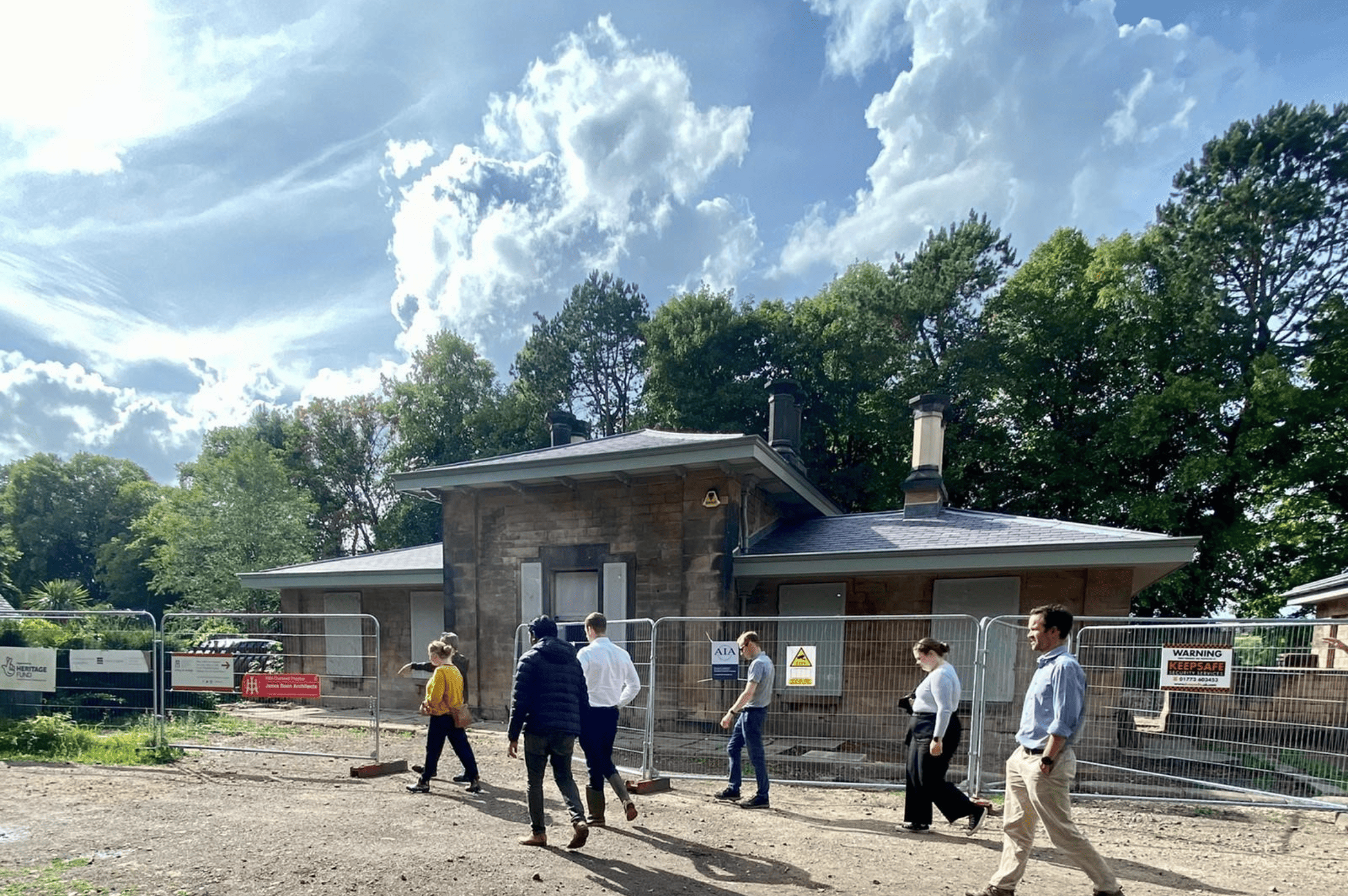

All cities are patchworks of architectural styles that reflect the changing fortunes and aspirations of a place. At a recent Marketing Derby event there was talk of a “renaissance” for Derby. Redevelopment schemes at Becketwell, the Nightingale Quarter (formerly Derbyshire Royal Infirmary) and the University Business School are well under way. Also in the pipeline are plans for Friar Gate Goods Yard, itself within the Friar Gate Conservation Zone. City centres are changing, and many would argue that Derby needs to move with the times. One issue we see, however, is the apparent disconnect between what heritage professionals or the ‘heritage lobby’ deem to be ‘harmful’ and what the general public feels. Furthermore, heritage professionals will often equate change with harm whereas this is far less likely to be the case amongst the general public, where progress is often seen as a ‘good thing’.

The heritage of our city is reflected and preserved successfully with schemes such as the restoration of the Victorian Market Hall and the success of the Museum of Making, showcasing our industrial heritage whilst also looking ahead. Sensitive repurposing of heritage assets such as the Old Post Office have resulted in a modern facilities like CUBO Work that address modern business and lifestyle needs.

Tall buildings are synonymous with cities and, if Derby wants to be taken seriously as a 21st century city then our skyline needs to reflect that. Over the past century Derby has in fact lost a number of tall buildings that accompanied the loss of its manufacturing industries, as its city centre changed in the early 20th century. Cities also need to densify in order to meet the need for more housing and to breathe new life into our cities. Whilst it remains to be seen whether 29 storeys is an appropriate scale of development, this is matter to be considered at the reserved matters stage when the detailed design and siting of the building can be properly assessed. We do, however, welcome opportunities for development that enhance and complement our heritage, creating a modern, vibrant city, that attracts new residents, visitors and businesses alike.

Megan Askham is a Planner and Richard Pigott is a Director at Planning & Design Practice Ltd.

All Images: Derbion/Leonard Design Architects